CHANGE CHANGE CHANGE (and how will these gardens be remembered?)

Would you live forever, never die

While everything around passes?

Would you smile forever, never cry

While everything you know passes?

Adrianne Lenker | ‘Change’ | Big Thief

This is being written in the first week of what feels like summer. Early May to be specific. Not actual, calendric summer, but that moment when the climate opens its arms for the first time in months, and gives you an overdue hug. Heat, light, sweat, flowers, flies, mild sunburn, and a big boost of natural energy from something (when will science discover humans have some kind of photosynthetic mechanism?).

This change into summer, for most living at our latitude, is a welcome thing, and brings with it a change in clothes, food, music, and the texture of conversations. As it happens, we’ve been talking shop with people in the industry, over the past few weeks, in pub gardens reoccupied by people, plants and midges. Aside from the pleasure of connecting with people again, it’s nice to be reminded – despite the access social media provides – of how much more of a feeling you get for any subject when you sit down and talk with people connected to it. And, whether it’s us, or those we’ve been meeting with, or whether it’s the season or something wider, a constant source of conversation has been around the idea of change and the question of whether the industry changing, and whether this is happening fast enough?

Without being drawn in to yes/no binaries, and clichés along the lines of change being the only constant, it does feel, at least, as if we are living within, or perhaps at least entering into, a moment of transition. If we place aside the bleak and often overwhelming data at the heart of global environmentalism, it is possible to track reasons for some grounded optimism.

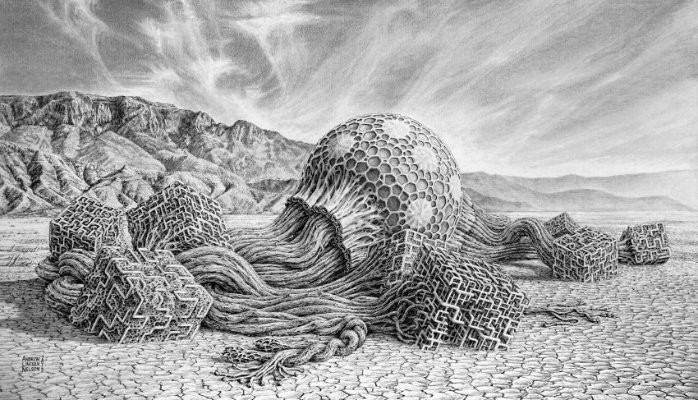

Sometimes these reasons can arrive in modest forms. We were recently given a seratonin rush, for example, by Duncan Nuttall’s drystone wall made of construction waste products. Packed with debris – ends of brick, broken garden ornaments (though unfortunately no gnomes), bits of hose, toilet seats, etc – the wall somehow encapsulates everything that the garden industry is getting right about progressive change. Considering how the moment of history in which you live will be viewed in the future can be an addictive thought experiment. In the case of now, are we witnessing a paradigmatic shift from a form of purism (cleanliness, precision, monoculture, certainty, straight lines) into something more ambiguous (imperfection, nuance, diversity, irregularity)? There’s no better example of this than the move away from the rectangular certainty of a 20th century skyscraper.

Recent advances in deep ecology – and our understanding of how complexity, diversity and messiness allows life to thrive (think mycelial networks, soil structure, gut biomes etc) – have translated into aesthetics. In this context, it’s easy, therefore, to see how garden design, through its use of inherently chaotic materials – the stuff of life – could easily be seen as one of the pioneering art forms of its age. It’s quite difficult for an artform to be political without straying away from its primary function of being a conduit for complex emotion. Through its embracement of a natural ideological counterpart in environmentalism, however, garden design starts to become a paragon for change without ever straying from its role of waking up our imaginations to the possibilities of a living, respiring form of art.

A garden can never last in the same way that, say, a painting can. This is, of course, part of the pleasure. Instead of preserving the moment of their creation and their creators, in a sealed frame, like recorded music, sculpture, etc etc; they are instead a dynamic chimaera bearing something like the genetic code of those who built them. Just as the rabbit leaves its legacy upon the world in the warren that it builds (for philosophers of ecology like Timothy Morton, the warren is an expression of the rabbit’s phenotype, literally part-rabbit), the gardener leaves something of themselves in their creation. The rose bush a great-grandmother plants is a living expression of her being long after she has stopped existing in the same time and space. This moment for gardening, therefore, cannot be experienced in the same way that paintings from a century ago can, but it will be interesting to see how their impact upon culture will be remembered.

How will gardens such as Tom Stuart-Smith and team’s masterpiece at Knepp be seen in several decades when it’s been left to demonstrate its homage to diversity and sustainability? Nigel Dunnett’s visionary sustainable drainage system in Sheffield? These congruences of form and function, politics and art, design and its opposing force, feel like important influences for a wider culture attempting to come to terms with the enormity of the task for civilisation. They answer the call, often levied at pessimistic and scaremongering environmentalism, to inspire change rather than to scold.

Perhaps, should the more chilling predictions become manifest, it will all become obliterated in forest fires or oceanic floods? But if it doesn’t, and these are some of the tendrils for positive change, it is perhaps worth thinking more about how, as a wider industry, we do more to follow the example of those who are pushing things beyond what we’d have imagined were possible not so very long ago.