In Search of a Nature Cure

Written by Max Crisfield

How gardening and nature connection might transform our mental health

Recently, as I scanned my bookshelves for Richard Mabey’s seminal memoir Nature Cure, I was struck by how many books we had assembled on a similar theme: the relationship between the natural world and our human well-being. Alongside Nature Cure – to my mind the high watermark in this niche nature writing sub-genre – I spotted The Outrun by Amy Liptrot, H is for Hawk by Helen Macdonald; Plot 29 by Alan Jenkins; The Salt Path by Raynor Wynn; I am an Island by Tamsin Calidas. And so on…

Though each of these stories is personal and therefore distinct, they share a recognisable narrative arc in which the writer experiences a period of emotional, spiritual or mental dissolution, then begins a slow process of rehabilitation by connecting or reconnecting with nature.

It is not surprising that I have found myself drawn to these stories. Though I don’t have a bestselling memoir to show for it, I too have, at times, experienced debilitating downturns in mental health and found solace in nature. In my case, it has been gardening, the simple act of sowing, growing and nurturing plants, that has smoothed the edges.

Not that any of this is new. Since time immemorial we have known, or at least implicitly understood, that working the land and in particular making gardens can foster positive change.

In the ancient world they knew a thing or two about this relationship.

Two millennia back, Chinese Taoists believed nature connection and in particular the creation of gardens to be a stepping-stone on the path to spiritual awakening. Harmony – with oneself, with one’s fellow man and with one’s natural environment – was key to the cultivation of spiritual, physical and psychological well-being.

As early as 500 BC the ancient Persians were creating formal, ornamental gardens whose principles of architectural and horticultural harmony are echoed in our own contemporary healing gardens.

In sixth-century Japan, during the reign of Empress Suiko, ‘meditation gardens’ were designed and curated for Buddhist Dharma practice and mindful contemplation. Later, Zen gardens, with their minimalist aesthetic and subtle symbolism, were cultivated to create optimal conditions for meditation and quiet repose.

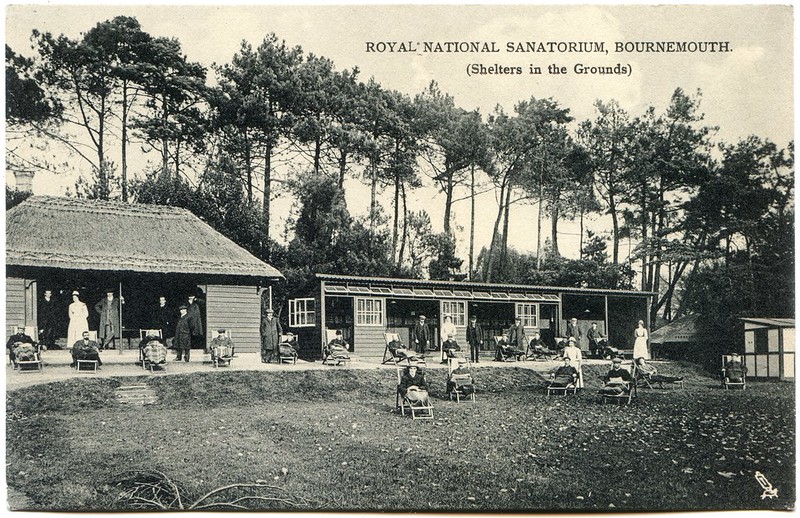

In the West, though the idea of the garden as a place of healing dates back to mediaeval Europe, it really gained traction in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when many medical institutions – hospitals, asylums and sanatoria – began to consider gardens, courtyards and green spaces as integral to their therapeutic efficacy.

The early twentieth century saw the introduction of outdoor hospital wards for TB patients and the rise of the ‘open-air school’ movement. During both world wars, many soldiers suffering from shell shock (PTSD) were treated using programmes that prefigure modern day horticultural therapy practice.

Today, the idea that creating, nurturing or simply spending time in a garden is good for one’s mental or spiritual health is an accepted mainstream proposition. Gardens are recognised not only as ornamental spaces that give sensory pleasure but as meditative, restorative, even sacred places.

After a long hiatus, during which time many of our modern health institutions seem to have ‘paved paradise and put up a parking lot’, we seem to have once again grasped the nettle. The last decade has seen some high-profile garden settings developed in our contemporary hospitals – Cleve West’s design for the Horatio’s Garden at Salisbury District Hospital; the Chris Beardshaw-designed garden at Great Ormond Street; Dan Pearson’s Maggie Centre garden at Charing Cross hospital in West London, to name but a few.

The concept of the ‘quiet garden’ as a place of sanctuary from the hurly-burly of modern life is also gaining momentum. The Silent Space project (silentspace.org.uk) was conceived in 2016 to create dedicated silent areas within public gardens (a bit like the quiet coach on a train) where one can sit, contemplate and simply be-in-the-moment without distraction.

Likewise, the Quiet Garden Movement (quietgarden.org) provides access to over 300 gardens and outdoor spaces worldwide, each designed to encourage contemplation, meditation and reflection.

The Guide to Silence project (guidetosilence.org) has identified numerous open spaces, gardens and walks in cities across Europe, which promote well-being and tranquillity. In June 2021 London’s Hampstead Heath was awarded Europe’s first Urban Quiet Park status by Quiet Parks International, an organisation dedicated to preserving silent areas within urban parks, wilderness spots and nature trails.

What seems to have brought about this change is that the science, and particularly the neuroscience, has finally caught up with our ‘felt sense’. We now have the hard evidence to back up what we gardeners and nature lovers have instinctively ‘known’ all along. In 2020, Sue Stuart-Smith, psychiatrist, psychotherapist and garden maker, published the definitive book on this subject, The Well Gardened Mind. Employing a mix of contemporary neuroscience, psychoanalysis and personal case studies of trauma, addiction, anxiety and depression, she explores how gardening can radically transform our lives.

Until recently I’d never really questioned why or how gardening and working in the great outdoors had affected my own mental health. I just knew that it worked and that was enough. But the more I think about it, the more I believe it has something to do with optimism. Gardening, as I described in a recent piece I wrote for Bloom magazine, is an act of faith. It is by its very nature future oriented and therefore hopeful. What we sow now, in a very literal sense, we reap further down the line. A garden provides a safe, contained space in which the gradual and impersonal processes of birth, growth, senescence and renewal are played out in real time, and this can be both inspiring and liberating.

Change can be a major stumbling block for anyone suffering mental ill-health, but in a garden one is constantly reminded that impermanence is the natural order of things. It pervades every process, every gesture, every action. Seeds germinate, weeds grow, flowers bloom, fruits form, leaves fall, seasons come and go. Everything changes. You can’t sidestep it. But if you pay mindful attention to its pulses and rhythms, over time it can be transformed from an object of fear to an ally.

As I slot Richard Mabey back on the shelf, between Mark Hamer’s From Seed to Dust and Roger Deakin’s Waterlog, I realise that this little collection of ours hasn’t grown by happenstance. For me, at least, there must have been something subliminal at work here, some sense of kinship in this shared celebration of nature’s restorative power. Perhaps by reading these accounts I could acknowledge that my own experience of nature cure, prosaic though it might seem, was part of a bigger picture. Just as Helen Macdonald had salved her grief by bonding with a wild goshawk, just as Richard Mabey had made peace with his depression by encountering a new wild landscape and rekindling his joy of writing, my own humble act of creating and tending gardens had provided balm for a bruised soul.